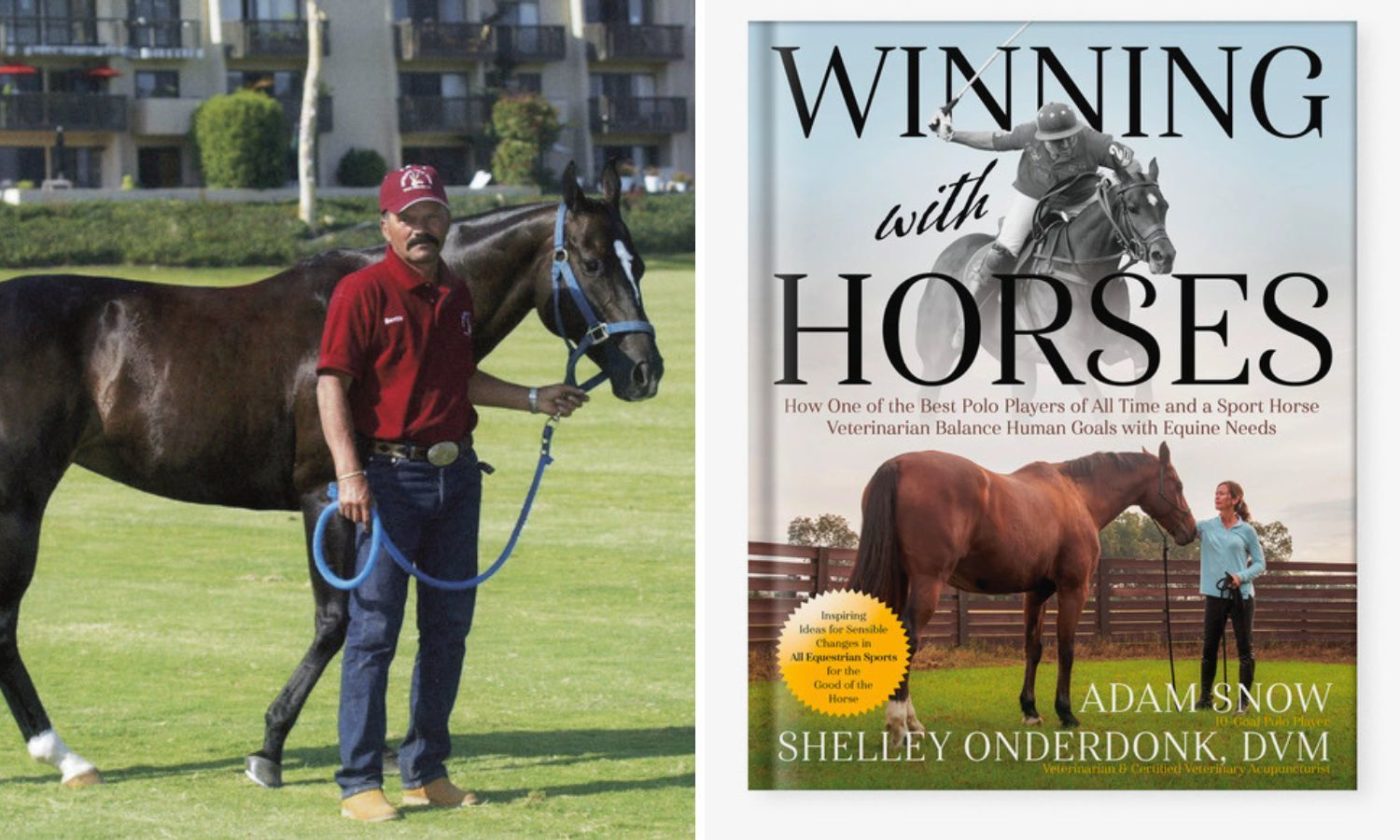

The following story is an excerpt from Winning with Horses, by Adam Snow and Shelley Onderdonk, DVM.

Hale Bopp

About halfway through my 2009 Florida high-goal season, Hale Bopp came up lame. At the time she was 17. Our team’s veterinarian assessed her, found degenerative changes in one front ankle, suggested injecting that joint with hyaluronic acid and cortisone, and said she’d be ready to go for our next game in three days’ time.

“Don’t I have to give her two to three days of stall rest after a joint injection?” I asked.

“That’s what some do, but I must have injected…” he made a gesture with his hand that indicated countless numbers (that return to work right away) “…and no problems.”

That should have been a red flag.

Shelley was in Aiken with our three kids, as well as the “turnouts”—she had enough on her plate. I felt it was unfair to ask her advice if she couldn’t put her hands or eyes on the mare.

Hale Bopp had hardly missed a chukker since she came to me over a decade before as a sprightly six-year-old. But what could I expect, with the number of games she had played for me over the years, and her age? There weren’t many, if any, late “teenagers” playing in the US Open. And maybe the injection would help her feel better. And this veterinarian did have years of practical experience—all over the polo world, in fact. Couldn’t I trust that?

And I really wanted to play Hale Bopp in our next game.

The beginning of the season had been tough. I was 45 years old, about to turn 46, and it was the first time I noticed myself sometimes getting “out-quicked” on the field. After one loss, I even admitted this sensation to my teammates. It was an upsetting realization, but it helped to voice it. And I had to live with the reality that I was getting old(er).

“In season,” like at that moment with Hale Bopp, I pretty much only thought about my next game. The mare may no longer have been the fourth chukker dynamo who I could bring back for overtime—she’d naturally lost a step or two—but she still turned like a top, and more than anything, she gave me confidence. I was starting her in the first chukker of most matches.

And, on her, I still felt quick out there.

So my relief at hearing the team veterinarian tell me she could play buried my concerns about safe protocol. And I said yes to the injection.

That afternoon the team veterinarian administered the intra-articular dose of hyaluronic acid and cortisone. The ankle was wrapped and Hale Bopp rested that night in her stall as usual. The next morning she went on a walk set, and a light trot, with her normal group of horses—her “friends.” And that afternoon the ankle had additional swelling and heat. There was an attempt to treat the “flare” with injectable antibiotics; her return to work was halted.

Shelley arrived from Aiken for a pre-scheduled visit, took one look at our mare and said, “We have to get her to a hospital as soon as possible.” Shelley was afraid the joint had gone septic.

I remember loading her onto our trailer—one horse alone in a space big enough for 12—and driving her to Dr. Byron Reid’s urgent care facility back among the canals in Loxahatchee, Florida. She stayed for five days, underwent surgery, had her ankle lavaged multiple times, and for the first 36 hours there was some question about whether she would survive.

I hated myself for putting Hale Bopp in the situation she was in. Visiting her each day—seeing her alone and confused, in a strange place, and obviously in a lot of pain—made me cry. I began to truly question what I was doing. I wondered whether high-level competition, and the pressures and demands on this horse, and other horses, were truly worth it. Honestly, at that moment, I would have given all my successes back to save Hale Bopp.

Writing these words, even now, I feel a pit in my stomach. For what had I put her in that situation? So I could continue playing a 17-year-old mare who had given me her heart and soul for eleven years? It was worse than that, because I had agreed to overlook safety protocols, with the short-term interest of not missing even one game on her blinding me to what I knew to be right. I couldn’t blame the veterinarian. He had been hired by the team, and helping our team win short-term was his primary aim. Injecting the joint may have been his suggestion, but it was my decision. An owner is ultimately responsible for the welfare of his horse. In this case my “next game selfishness” had a huge cost, because it meant the end of my favorite mare’s playing career. And when I saw her in the hospital, I would gladly have given up ever being able to play her again, if it meant I could take back my mistake. My prayer was simply that Hale Bopp would have the ability to live contentedly again with her friends for the rest of her days. It put things in perspective when her life was on the line.

There had been one other occasion when we thought Hale Bopp’s life was in jeopardy. But that time had been on the playing field, where accidents can happen. At the time she was eight or nine years old and we were playing the Sunday, 3:00 pm game at Palm Beach Polo and Country Club.

There was a quick change of direction in front of the stands, and Hale Bopp turned so fast that an opponent caught us from behind, and we went down in a heap. When I picked myself up off the ground, the first thing I saw was my mare standing on three legs, holding one foreleg in the air like it was broken. The next thing I saw was my groom, Bento, who must have raced out from the sidelines upon seeing the wreck. But then I noticed that he was wielding one of my spare mallets like a club and demanding, “Quien fue?” (“Who was it?”) Thankfully, nobody dared tell him who had hit us because he looked ready to take matters into his own hands. Shelley was out there, too, and that was a huge relief. Not only was she a veterinarian who loved this mare as much as I did, but she was calm in a crisis.

The emergency van drove out, we stripped Hale Bopp’s tack, found a halter, and Shelley led our mare, hopping, three-legged, up the ramp of the trailer. Shelley rode in back with Hale Bopp to provide some comfort on the short trip to the Palm Beach Equine Clinic. Of that ride Shelley remembers two things: the cacophony of riding in the back of an aluminum gooseneck trailer (every bump made all the moving parts rattle) and observing Hale Bopp as she began to gradually bear weight again on her front leg.

By the time they reached the clinic and Hale Bopp was unloaded, the mare was barely limping. The radiographs were negative—no fractures. And when Bento showed up in my rig after the match, Hale Bopp climbed on board, sound as a bell, to rejoin her friends and her routine. She had been badly “stung” in the accident, but we had dodged a bullet.

Back in Loxahatchee at Dr. Reid’s hospital, Hale Bopp’s situation gradually improved. Of course it would—she was nothing if not a fighter. By the end of the week, I was able to trailer her back to our barn. She was wounded and lame, but the infection had been beaten. And my prayer had been answered: she would be able to live out her days on pasture at our farm.

There were big offers to buy her as a broodmare. We were asked to ship her to Argentina where they could take embryos and mass produce as many little Hale Bopps as possible. But even though we were offered half her progeny, my moral compass (Shelley) wouldn’t let me even consider it. We (I) owed Hale Bopp the best home I could give her for the remainder of her years. And, if we ever decided to breed her, it would be as natural a process as possible.

For eleven more years she lived contentedly on our farm. Her playing days were over, but gradually her ankle got better. And it was a joy to watch her short-strided burst of speed as she galloped toward the gate to ambush her feeder. If it was me, I usually took time to stroke her coat or rub her back for a bit while she tossed Equine Senior and beet pulp from her bin to the ground. And each time I laid my hands on her, all those memories of our playing days together came rushing back.

This excerpt from Winning with Horses is reprinted with permission from Trafalgar Square Books. To get a copy, go to: https://trafalgarbooks.com/products/winning-with-horses.

Whether you've brought your horse up from Novice or took on the ride later in their career, getting to your first five-star on a special partner is a huge accomplishment.

Are you following along with the action from home this weekend? Or maybe you're competing at an event and need information fast. Either way, we’ve got you covered!

The United States Eventing Association, Inc. (USEA) is excited to announce that Stable View has been selected as the host venue for the first standalone USEA Intercollegiate & Interscholastic Eventing Championships which will take place in 2026 and 2027.

The U.S. Equestrian Federation (USEF), in collaboration with the United States Eventing Association (USEA), has announced a new national review process for innovative frangible cross-country jump designs. This initiative aims to support and streamline the evaluation and potential use of novel frangible devices at the national level within the United States.