Now On Course: Korbin the Conqueror Beats the Odds

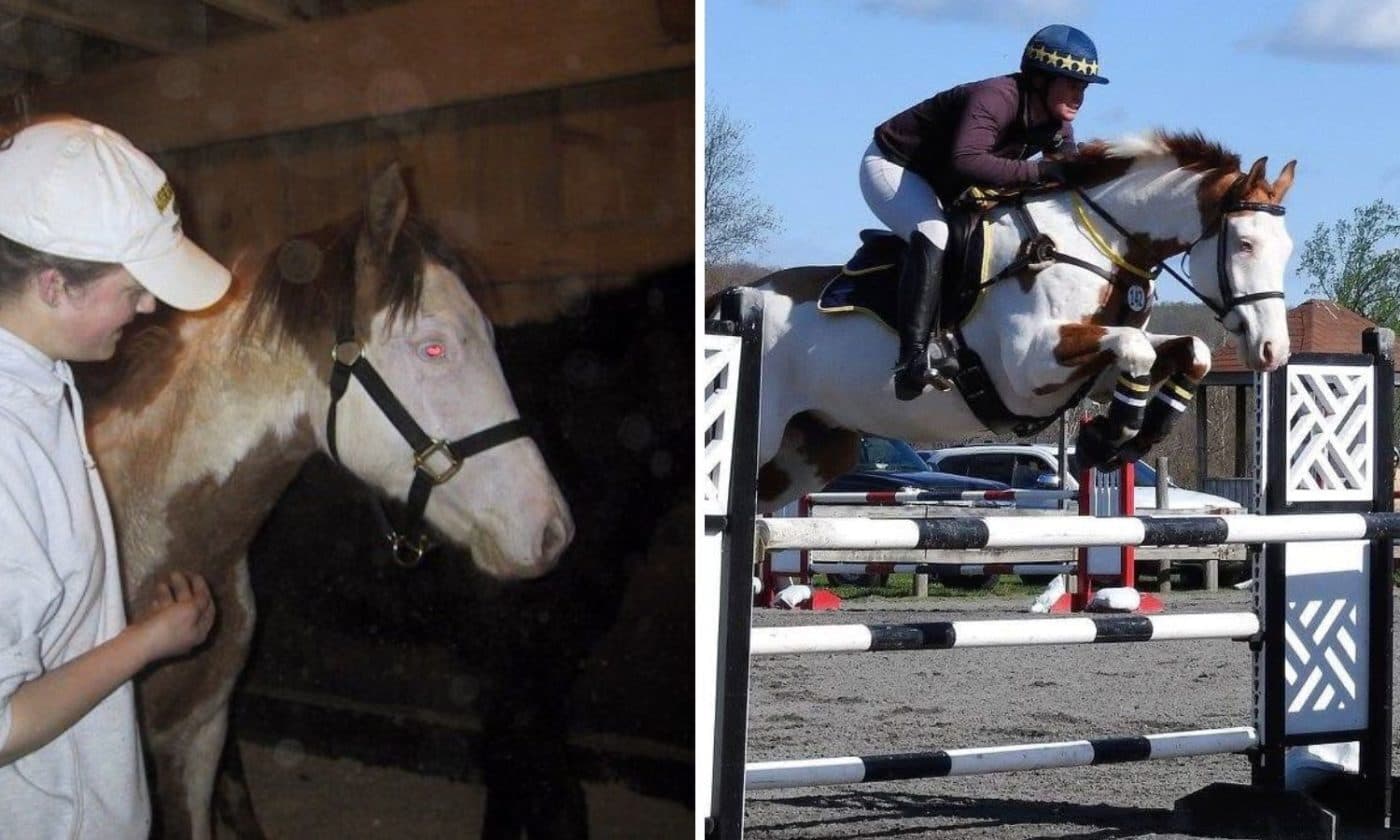

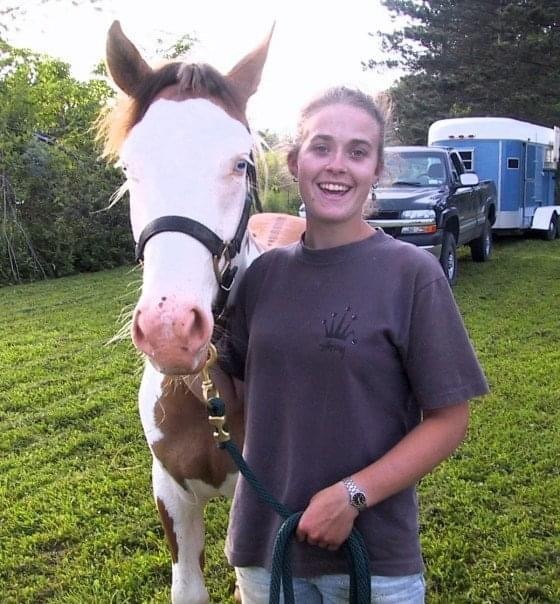

Suzannah Cornue’s Korbin has always stood out in the show ring, thanks to his bright blue eye, bald face, and chestnut pinto coat. However, what really makes this pinto gelding one of a kind isn’t how he looks, but what he’s been through.

Korbin has had more brushes with death than the average horse. For him, life was almost over before it even started. The year was 2003. Korbin was a PMU (pregnant mare urine) foal that had found his way to the auction house. A young college freshman living on her family’s farm in upstate New York at the time, Cornue had heard about a trailer load of these foals coming her way.

“We had heard of this lady that had a ‘rescue.’ She would go out west and go to the meat auctions, where they would send all the PMU mares and foals when they were done with them. She'd pick up a bunch of the weanlings after they pull them from their moms,” Cornue said. “We went to look at them, and I swear it was like we were rescuing them from the rescue.”

Cornue described the lower level of that overcrowded bank barn as a dungeon “stuffed with babies. It was terrible. They were up to their knees in poo,” she recalled.

Stepping into the crowd with hopes of finding her next fox hunter, Cornue was looking for a large foal with performance potential. Korbin, who is today only 15 hands high, was not her first choice, but he refused to be left behind.

“I was not looking for a tiny little paint horse. I’m looking around, and I’m kneeling down there, and they’re all terrified. I’m trying to get up and look at one I was interested in. And Korbin would come up behind me, touch my back, and when I turned around to look at him, I’d see his little blue eyes. He’d be like, ‘Oh my God!’ and then run away,” Cornue said.

At the end of the day, Cornue had picked out her foal—it wasn’t Korbin. Fate (and Mom) intervened. “My mom said, ‘They’re only $300 a piece. If you’re gonna get one, you might as well get two.’ Korbin was the second foal I brought home,” Cornue said. “He picked me out, you know? He was like, ‘No. You’re going to take me.’ ”

It was a good thing that Cornue had the optimism and ignorance of youth on her side, as the two foals were about to give her a run for her money. “They were straight feral,” Cornue said. “I kept them both in the same stall together for the first month, just to be able to handle them.”

“I was kind of a backyard kid,” she continued. “I just taught myself really. I got these two feral babies. I didn't know what I was doing. I just figured it out—it was probably the best way to learn.”

Working with the babies was an exercise in understanding and patience. Cornue would work with them every day until they were able to be handled enough to be turned out. “They were disgusting. I mean, they were just awful. Skinny and emaciated with matted hair and poo all over them. All you wanted to do was give them a bath and make them smell better, but you couldn't touch them.”

Once they were able to be turned out to pasture, Korbin decided he liked the company of humans, and the excitement of fox hunting, a little too much. “He started jumping the fences out of our paddocks,” Cornue chuckled. “We used to host a bunch of fox hunts from our farm. We would go out fox hunting, and he would jump out and come and join us. There were times I had to be called home from school to catch my bad horse.”

Together, Korbin and Cornue tried a little bit of everything before they moved down to Maryland and began eventing together. “I got him going to the point where he was a basic Training level packer. My plan was to sell him as a Training level packer,” Cornue said.

But again, fate had different plans. A young professional working on establishing the business that would one day turn into Destination Farm, Cornue’s life was in a state of flux.

“I had had a couple other young horses coming along. I ended up selling one, and another one ended up going neurologic. I had to put that one down. So here I am, left with Korbin. I said, ‘I guess let's see what he can do,’ ” she said.

Korbin conquered every challenge Cornue put in front of him. “I took him around some Prelims, and, well, those were kind of easy for him. I thought, ‘OK, well let's get your passport and get microchipped and try to do some FEI.’ We did a couple of one-stars, which now would be a CCI2*.”

Next, Cornue put some Intermediate tracks in front of the intrepid blue-eyed pinto. He popped around like he had been bred for it. Together, the pair tackled a CCI2*, which would now be classified as a CCI3*.

“It was easy. He was really good,” Cornue said. “It wasn’t like he was wild. You just felt like a little kid on a pony riding him around those tracks.”

When Korbin was 15 years old, Cornue entered them in the CCI2* at Maryland (now CCI3*).

“I went to go jog up for in-barns,” Cornue said. “The vet that was doing in-barns had seen him a handful of times at other events. She said, ‘I know him, and I know that he's not a big mover, but watching him jog today, I'm not gonna say he's unsound, but he doesn't look like himself.’ ”

“So, I went on ahead, and I got on for dressage, and I started warming up for dressage,” Cornue continued. “And I was like, ‘She's right. He doesn't feel right.’ ”

After scratching from the competition, Cornue trailered Korbin home, which was luckily right across the street, and called her vet. The news wasn’t good. At some point, Korbin had fractured his left hock.

“The vet was like, ‘I swear to God, if I didn't know this horse, I would look at these X-rays and say this horse isn't sound enough to even go Novice, but he’s just been popping around,’ ” Cornue said. “His hocks were basically, at that point, almost fused, but he had been going around totally fine.”

Opting to take her vet’s advice to give the horse a year off and see how he came through on the other side, Cornue put Korbin out to pasture with a fly mask and sunscreen.

“Apparently, the amount of UV fly masks and sunscreen and everything over that year did not protect him from the sun because when I got him rechecked, the vet noticed little sores around his eyes,” Cornue said.

Unfortunately, Korbin’s white skin and pale eyes made him predisposed to skin cancer. Sure enough, he had the beginnings of skin cancer around both of his eyes. Cornue brought him to Dr. Catherine Nunnery who performed surgery to cut out the cancer as much as possible.

“He was really sound. I was just starting to work him again when all of a sudden, the bone around his right eye started blowing up,” Cornue said. “We went in, did a bone biopsy, and sure enough, the cancer had leached into the bone and turned into bone cancer.”

The majority of the time, a diagnosis like this one is a death sentence. Dr. Nunner prepared Cornue for the worst and told her to expect him to become neurologic and pass away.

“You could tell he was really not feeling well. There was one day I called Dr. Liz Reese, my vet, to discuss putting him down,” Cornue said. “He was looking awful. You could tell he felt awful, and I literally had a day set up that we were going to put him down.”

But, in true Korbin style, he wouldn’t hear of it. “That morning, I woke up. It was a beautiful day. I get to the barn, and he is bright and cheery. I called Liz, and I decided to just wait. He was having a good day. Let's just wait. And then after that he never really progressed any further,” Cornue said.

While the fact that Korbin’s cancer never progressed was her own little miracle, Cornue spent every summer waiting with bated breath. She bought the latest and best UV fly masks to protect his skin and slathered him with sunscreen. But every time summer came around, she worried it would be his last. At that point, Korbin had been retired for five years. Cornue would get on him from time to time to go for a hack and enjoy her old friend. But she could tell his eye, while not getting worse, was still causing him pain.

By the spring of 2022, Korbin was very sound, but Cornue could tell the eye was still bothering him. She called Dr. Nunnery and asked if taking the eye out would help.

After a three-hour standing surgery at the barn that was complicated by the bone growths, Korbin was without his right eye. “It was funny. As soon as he woke up from the sedation, you could just tell he instantly felt better,” Cornue said.

In fact, Korbin felt so much better that the day after his surgery, he decided to take himself for a joy ride, like he was once again a foal jumping fences in Cornue’s childhood farm in upstate New York.

“I just went out to give him a hug and see how he was doing. He's a good boy, and he was old and sick, so I had his stall door open. All of a sudden, he blew past me,” Cornue said. “He got loose with a bandage on his face. He galloped around on a tour of the farm. He ran down the driveway onto 85, ran up the road, went up our neighbor's driveway, and caused havoc all over their farm. Ran around back on 85—he stopped traffic. Then he came back up to our farm.

“‘You clearly feel better, you’re going back to work,’” Cornue said she told the little horse. “Five days later, I take the bandage off, and all of the stitches in his eye had popped. I was left dealing with a gaping hole in his head that I had to wrap every day. I had to stuff his eye socket with Furazone. It took a long time to heal, but it healed. I put him back to work, and he feels great.”

At 20 years young, Korbin officially came out of retirement. “You could just see the instant that the pain was gone, he was like ‘I’m good, I’m ready to go,’ ” Cornue said.

In 2023, Korbin and Cornue ran around a handful of Novice events. In 2024, they started off with one Novice competition but spent the rest of the season competing at Training level. In 2025, Cornue is continuing to compete with him at Training, but Korbin also moonlights as a confidence boosting ride for some of Cornue’s students and working students. With the removal of his eye, Korbin has a new lease on life.

“[Losing an eye] didn't really seem to affect him much,” Cornue said. “We had to relearn how to see a bank. It's actually the hardest in dressage. If his right side, where he doesn't have an eye, is on the outside, he can't really see the rail. So, I really have to ride that one side of him. I definitely have to be conscious of my blind turns on that side.”

When Cornue first met Korbin, she was only a college freshman, having just graduated from high school. Now, 22 years later, she runs Destination Farm with Natalie Hollis, which offers boarding, training, sales, and more. Korbin has been by her side through every phase of her riding career.

“We both moved down to Maryland together and started all this together,” Cornue said. He’s been with me through all of it. Through being a working student and getting my first training job, on to getting our own farm and having our own training and working student program and a farm and all that. He’s been my constant, my staple, this whole time.”

You can find Korbin and Cornue competing all over Area II. At their last outing, Cornue and Korbin tackled Training level at the Morven Park Spring Horse Trials (Leesburg, Virginia). While she had been worrying about how he would handle the course, Cornue said her worries disappeared when Korbin was wild in the start box and flew around the cross-country course.

“I don't know how many more he's got in him, but if he wants to keep being wild, I'm just gonna let him continue. I figure he'll tell me when he's done. I don’t take it for granted. He's beaten a lot of odds, but who knows how many [years] I have left with him,” Cornue said.

Looking back on their long partnership, Cornue said one thing she’s learned from Korbin is to never judge what a horse can do by how they look.

“I always tell everybody, ‘Don't put a limit on any horse.’ I think a lot of people do that—they just look at a type of horse, and they instantly, in their mind, put a limit on them. Go see what they can do first.”

Korbin has certainly never let anyone, or anything, hold him back.