This article originally appeared in the March/April 2020 issue of Eventing USA magazine.

Dr. Elizabeth MacDonald, Clinical Instructor of Equine Medicine at Virginia Tech’s Marion duPont Scott Equine Medical Center (EMC) in Leesburg, Virginia, began her presentation on gastric ulcers by saying, “My goal is to not just tell you about what’s out there but make you understand the stomach, its job, how it functions, and what its role is so that we can better understand how we diagnose disease and how we can treat and prevent.”

MacDonald started by explaining the function of the horse’s stomach. The equine stomach provides an essential function as a short-term reservoir for food before it enters the intestinal tract. “The stomach is quite small compared to the actual size of the horse, so it can only hold 10-15 liters, which is a small amount when you consider how big the horse is and how much it takes in,” she said. While the food is in the stomach, chemical and enzymatic digestion begins with the help of acid secreted in the stomach.

The stomach is divided into two portions: the upper portion is called the squamous mucosa and the lower portion is called the glandular mucosa. “The squamous mucosa is a simple epithelium, the same epithelium as in the esophagus,” MacDonald elaborated. “It’s responsible for mixing and moving the food around. It has no way of protecting itself and it’s highly susceptible to injury – it’s not designed to be exposed to what the lower portion produces.”

The lower portion of the stomach – the glandular mucosa – produces the hydrochloric acid that breaks down the food. “In this area, we have cells responsible for producing hydrochloric acid which helps beak down food and produces the acid in the stomach,” MacDonald explained. “It also produces gastrin, pepsin, all sorts of digestive enzymes. It’s also able to produce mucous and bicarbonate. Mucous is that thick, viscous material that is able to line that region of the stomach and protect it. Bicarbonate is a basic buffer, so it balances out the acid that this portion of the stomach produces.”

The way that horses secrete acid in their stomachs is quite different from the acid secretion process in humans. In humans, acid is secreted when food enters the stomach and secretion stops as the stomach empties. Acid secretion in the horse happens all the time. “Your average horse produces approximately 1.5 liters of bile every hour,” MacDonald said. “If you’re not putting anything into their stomachs, they’re still producing acid that’s just sitting there. That’s a large amount of acid that just keeps sitting in their stomach.”

How do horses manage all that acid? Firstly, by eating continuously. Horses are grazing animals and their stomachs are designed to support continuous eating. “Consumption of roughage decreases the acidity of the stomach and chewing and swallowing stimulates saliva production, which also has buffering abilities. The horse has mechanisms to protect itself, but when we alter its environment and its diet it really affects how this system works.”

Horses can develop gastric ulcers, or Equine Gastric Ulcer Syndrome, as a result of too much acid in the stomach. Gastric ulcers can affect both the squamous and the glandular mucosa, with different causes resulting in ulcers for each. When gastric ulcers occur in the squamous mucosa, the most common gastric ulcers in horses, it is typically a result of too much acid in the stomach. “Because it has no way to protect itself, as the stomach becomes empty it gets exposed to the acid naturally in the stomach,” MacDonald said. “Another thing that can cause squamous ulcers is pressure in the stomach, for example when a horse is exercising.”

“The glandular mucosa has the ability to protect itself with mucous and bicarbonate production,” continued MacDonald, “so ulcers occur when there’s damage to the ability of those cells to produce mucous or bicarbonate. While they’re both in the stomach, we’re looking at two different approaches to the stomach – it’s very important when considering treatment.”

Risk Factors

What makes a horse more likely to develop gastric ulcers? “Long periods with no access to hay definitely affects them,” MacDonald said. “Diets that are high in grain and low and forage also make a difference. Intense or high speed training absolutely makes a difference – intensity is different for every horse, based on what their job is, so not everyone has to run really fast to get ulcers.”

MacDonald identified stress as another risk factor for horses developing ulcers. Everything from a ride in the trailer to a change in pasture-mate to moving to a new barn can be a potential stressor for a horse. “It’s always hard to interpret and every horse is very different.”

Illness can be another cause of gastric ulcers. “Any time you don’t feel well you might go off food, and this puts horses at risk for developing ulcers,” MacDonald said. “Prolonged use of some drugs, particularly non-steroidal anti-inflammatories – all of those drugs affect the blood supply to the stomach, so they absolutely contribute.”

Clinical Signs in Adult Horses

“Some adult horses show absolutely no clinical signs of ulcers,” MacDonald explained. “They seem to be able to cope with ulcers – they get on and can get through life no problem. Others have acute episodes of colic, or recurring episodes – those histories are the ones where we see ulcers. Poor body condition – maybe they’ve become a bit of a harder keeper than they used to be or their coat doesn’t look good. Maybe they’re a pickier eater – they’re still happy to eat their hay but they go off their grain. They can have a little bit of weight loss.”

MacDonald cautioned that you might also see small changes in attitude, like a horse that has become girthy that wasn’t before. “They don’t want to move forward under saddle – you put your leg on and suddenly they don’t want to move forward. That can be a clinical sign of many things, but it has been well attributed to ulcers as well.”

Grinding teeth can also be a sign of ulcers in horses. “If you see a horse in a stressful situation sometimes you see them grinding their teeth – that can also be a sign.”

“These are all vague signs that could be caused by lots of different things, but gastric ulcers have to be on your list of potential causes to rule out . . . the severity of the clinical signs don’t always correlate with the degree of ulceration.”

Diagnosis

There is only one way to definitively diagnose a horse that has gastric ulcers, and that’s a gastroscopy. “You have to visualize them,” MacDonald asserted. “You can have a suspicion if you have some of those clinical signs that I described, you can give your horse the appropriate treatment and they get better, but the only way to know for sure is to scope them.”

“We can never get the stomach fully empty – we’ve got all that bile constantly being produced – so we can never really appreciate the lower portion of the stomach because there’s no way to clear all the material that’s in there,” MacDonald said.

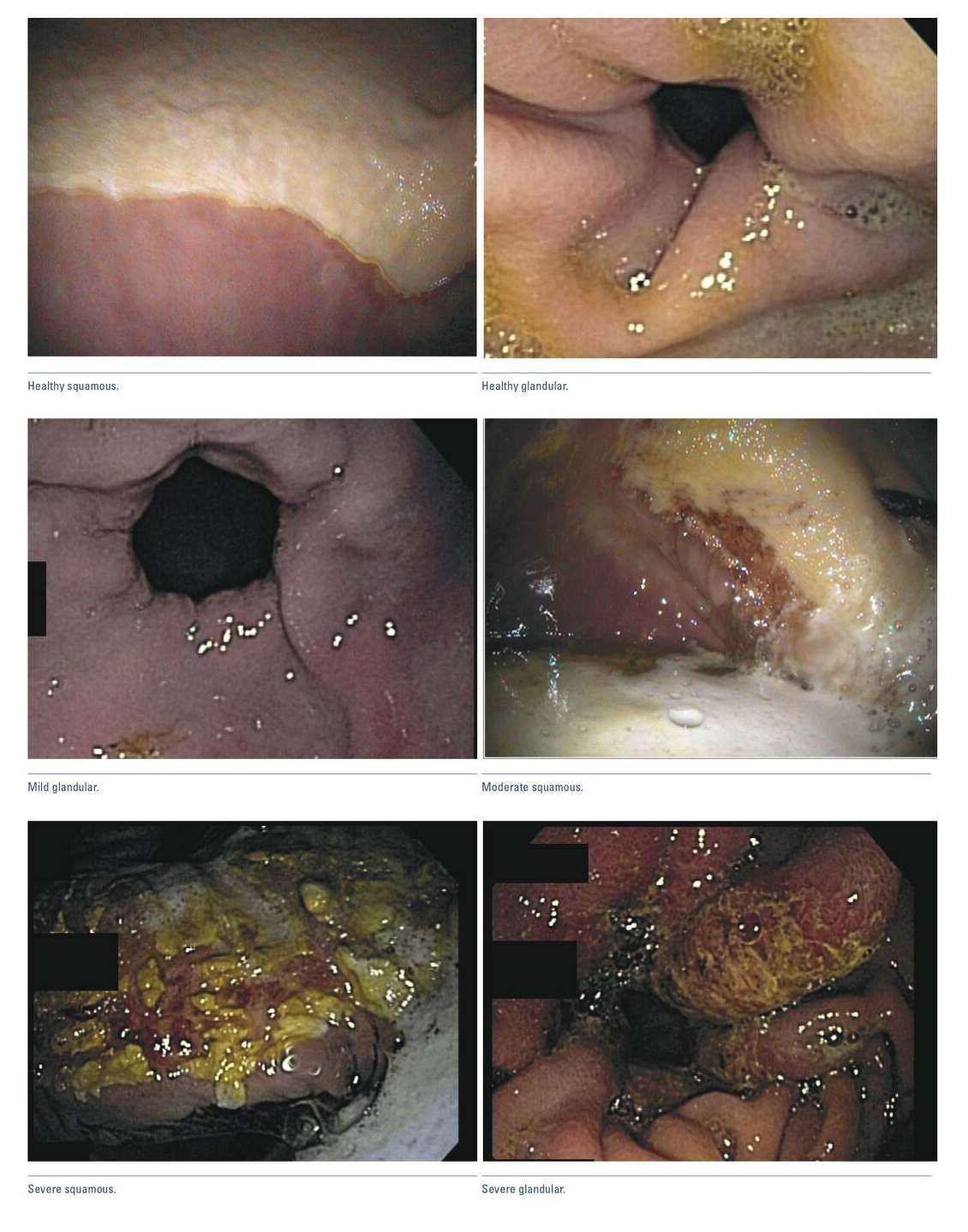

What does a healthy stomach look like? “You’ll have a light pink squamous mucosa, a smooth margo plicatus (which is the division between the squamous and glandular mucosa), and a darker pink glandular mucosa. This is what a healthy stomach should look like the whole way around.”

In horses with an unhealthy stomach, the first thing that may present is a yellow hue to the squamous mucosa, a condition called hyperkeratosis. “There is a fair amount of acid injury to the mucosa. It’s not severe enough that there are ulcers there, but it’s really yellow and been affected – the acid irritated it.”

From there, the condition can progress to where actual ulcers will form on the squamous mucosa. “They may not be very deep, but they can cover a decent amount of that section of the stomach,” MacDonald described. “While you don’t always see big lesions, you can actively see that they’re bleeding. You have an open wound that you’re splashing acid on. I can’t imagine that feels comfortable for the horse.”

Irritation in the glandular mucosa can appear as red and inflamed tissue. “While it doesn’t look major, for some horses that is enough to cause discomfort.” As the condition gets more severe, actual lesions will begin to form on the tissue. “As the tissue becomes inflamed, the motility decreases and becomes not as efficient, so that starts to make you worry about whether the stomach can empty appropriately.”

Treatment

We’ve diagnosed it, we’ve looked at it, now how do we treat these ulcers? “The two different parts of the stomach function differently and so we have to think about how we treat them differently,” MacDonald explained. “The part that often gets confused is that it’s often a multi-modal method of treatment. We can’t just give them drugs and this will go away – we have to change their management, their environment.”

What does ideal management look like to reduce the likelihood of ulcers? It starts with plenty of access to food – either grazing in a pasture or access to hay at all times. “I know we don’t have that all the time, but that is what horses were designed to do,” MacDonald said. “If you have an easy keeper that doesn’t need that much hay, put things in a nibble net. Pack that nibble net nice and tight and let them get their requirements throughout the day.” Adding in alfalfa can help because the calcium in alfalfa acts as a natural buffer.

Reducing grain intake can also help with reducing the acid content of the stomach. “When you feed a grain meal the pH of the stomach drops drastically and stays down for a period of time. If you have to feed grain, multiple small meals throughout the day can make a difference . . . another trick is feeding your hay before your grain so you have some buffering ability in the stomach because you give them a grain meal that’s going to rapidly drop the pH in their stomach.”

Limiting stressful events is another way to manage a horse with ulcers. “For every horse it’s different – you’ve taken their buddy away to a horse show and they’re gone for a week or you’re going on a trailer and they’re not used to it. We can only give generalized recommendations, but your horse can generally tell you when he’s stressed out.”

“If you’ve identified ulcers, you may have to alter their exercise routine while they heal and then make those management changes so when they finish treatment and start to go back into work we’re less likely to develop ulcers again. Maybe not working them as hard as frequently – you’ve got to look at what the horse is telling you.”

When it comes to looking at which medication to give to help combat ulcers, one must consider where in the stomach the ulcers are occurring. “Both parts of the stomach respond differently to treatment and have different effects,” MacDonald said. “One drug might not work for everything.”

The most common treatment is omeprazole, or GastroGard. “GastroGard is an FDA approved drug for the treatment of ulcers. When you use an FDA approved drug you know exactly what’s in the tube you’re giving your horse and you know that’s it’s proven to be efficacious. GastroGard works by blocking the pump that produces hydrochloric acid within the stomach.”

It’s important to note that only 70 to 80 percent of horses will show improvement after a 28-day treatment period – some may need to be treated for longer. “Every horse is a little different – the severity of the lesions are different,” MacDonald explained. “So we say treat for 28 days and then look again. It works – it’s very good – but it doesn’t fix every horse in 28 days.”

Ranitidine is another compound used to treat ulcers and was the drug of choice for ulcer treatment before GastroGard came around. It has a slightly different mechanism of action than GastroGard, but still act to suppress hydrochloric acid production. “Ranitidine is able to raise the gastric pH high enough and promote ulcer healing. The big thing is that there was much greater individual variation in response to the drug – not every horse responded exactly the same way. It also has to be administered every eight hours.” Ranitidine was recalled by the FDA in September 2019 due to the formation of a possible cancer-causing compound N-nitroso dimethylamine (NDMA) when ranitidine is exposed to heat. While there is no research indicating NDMA’s cancer-causing effects in horses, the recall of the drug has made it scarcer and therefore more expensive.

“Other options that we might consider are sucralfate, which bonds to the ulcerated mucosa and really makes a difference – it’s like putting a band-aid on it,” MacDonald said. “It definitely helps to promote healing. Misoprostol is a drug we’re learning more about and starting to use for glandular ulcers. It has a role in acid suppression. The one challenge is that it has side effects – it can cause abortion in humans and it can cause mild colic in horses.”

Antacids are beneficial, but they only have a temporary effect. “To keep your pH appropriate you have to give fairly large volumes more frequently. It’s maybe beneficial right before you go in the show ring or before you do intense exercise but it’s not going to be long lasting.”

What’s the best way to go about preventing gastric ulcers? Good management practices are key. “You can also use a preventative dose of GastroGard during times of potential stress. At least you know you’re making an effort, especially if your horse is prone to ulcers.”

Dr. MacDonald earned her Bachelor of Arts in biology from Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs, New York before completing her Bachelor of Veterinary Medicine and surgery with honors at the University of Glasgow in Glasgow, Scotland. She also received a Master of Science in biomedical and veterinary sciences from the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine in 2015.

Prior to becoming a clinical instructor at the EMC, Dr. MacDonald completed an internship at the New England Equine Practice in Patterson, New York and a residency in large animal internal medicine at the Marion duPont Equine Medical Center. She maintains professional memberships with the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) and American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP).

Did you enjoy this article? Want to receive Eventing USA straight to your mailbox? Members receive Eventing USA as part of their USEA Membership or you can purchase individual issues from the USEA Shop.

Having established clear lines of communication yesterday on the flat, it was time to take those tools to the jumping arena during day two of the 2024-2025 Emerging Athlete Under 21 (EA21) National Camp held at Sweet Dixie South in Ocala, Florida. The curriculum for the second day focused on the rider’s responsibilities and maintaining rideability.

“There’s got to be things that you believe to your core,” EA21 Director of Coaching David O’Connor began on the first day of the 2024-2025 Emerging Athletes Under 21 (EA21) National Camp held at Sweet Dixie South in Ocala, Florida. “For me, that’s communication.”

This week 12 talented Young Rider athletes from all over the country have gathered together in Ocala, Florida, for the 2024-2025 USEA Emerging Athletes U21 National Camp (EA21), led by EA21 Director of Coaching David O'Connor! These riders were hand-selected following the five USEA EA21 Regional Clinics that took place in the summer of 2024 and will spend the week immersed in an educational experience like no other with classroom sessions, hands-on learning led by industry experts, and in-the-saddle instruction facilitated by O'Connor. The National Camp kicks off tomorrow on Dec. 31, 2024 and will run through Saturday, Jan. 4, 2025.

USEA CEO Rob Burk sits down with Podcast Host Nicole Brown to talk about some of the key moments from this year's USEA Annual Meeting & Convention, which was held Dec. 12-15 in Seattle, Washington, including keynote speaker Tik Maynard's presentation, rule changes, accessibility and inclusivity, and more!