The Anatomy of a Joint

“Joints are very important because they make locomotion possible,” said Dr. Maureen Kelleher, Clinical Assistant Professor of Sports Medicine and Surgery at Virginia Tech's Marion duPont Scott Equine Medical Center (EMC) in Leesburg, Virginia. “Certainly there are other things involved, like muscles, tendons, and ligaments, but in order for the horse to move he needs to have bendable appendages and that’s where joints come into play. They transmit a lot of force and they allow the skeleton to move.” Because joints play such a crucial role in the horse’s ability to perform, caring for his joints is likewise an important part of ensuring his success.

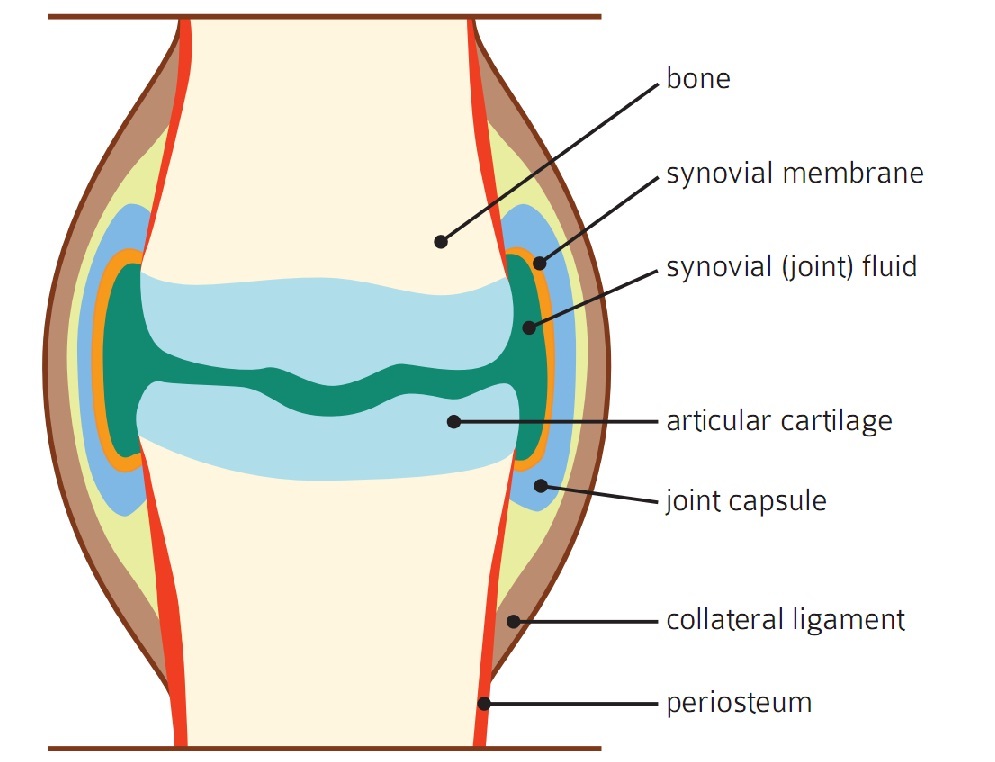

The first step to understanding how best to care for the horse’s joints is to understand the anatomy of the joint – all the different pieces that come together to make the joint healthy and able to accomplish its job. There are five major components of the joint – the joint capsule, synovial membrane, synovial fluid, articular cartilage, and the subchondral bone – and, working from “out to in,” Kelleher described the design and function of each.

“The joint capsule is a very thick, fibrous tissue, and it helps impart the shape and the stability to the joint,” Kelleher said. “There are lots of nerve endings and lots of vascular supply. The nerve endings are very important; they help the horse know where the joint is in relationship to the rest of his body and in relationship to the world around him.”

“The inner layer is the synovial membrane, which is really actually very thin,” she continued. “It’s only a few cell layers thick, but it’s responsible for feeding the joint and protecting the joint. The blood vessels in the synovial membrane are responsible for shuttling waste products out of the joint and shuttling nutrition into the joint. Also, in the synovial membrane, some of the cells are responsible for producing growth factors and anti- and pro-inflammatory proteins, and signaling molecules in response to normal physiological trauma and signals as well as non-physiological trauma and signals.”

“Cartilage is what covers the subchondral bone and it is composed of a few things: collagen fibers, water, and hyaluronate, and it also has a matrix of glycosaminoglycans,” Kelleher explained. “The collagen fibers give it a firmness and a stiffness and then the water gives it a bit of compressive nature. We want our cartilage to look like a smooth, white, glistening, gliding surface.”

Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), for example, chondroitin sulfate and keratin sulfate, are part of the matrix within the cartilage. Chondroitin sulfate and keratin sulfate bind to hyaluronan, which in turn connects to the collagen fibers. “The GAGs encourage production of more GAGs as well as the production of hyaluronan and collagen, and they produce enzymes that prevent the breakdown of GAGs, hyaluronan, and collagen in the joint.”

“Subchondral bone is a thin layer of bone adjacent to the articular cartilage, and it gives structural support to the cartilage and is a bit stiffer than normal bone. The rest of the bone has a bit of flexibility and give to it, but the subchondral bone is fairly rigid. It is rich in vascular and nerve supply which helps with telling the joint, ‘Hey, there’s something wrong here that we need to fix.’”

The final of the five different elements that make up the joint is the synovial fluid, which fills the space between the synovial membrane and the articular cartilage. “The synovial fluid is a thick, viscous liquid that has hyaluronan in it, the products that are filtered from the blood through the synovial membrane, and the products from the cartilage that are on their way to the synovial membrane to go back to the blood supply and leave the joint.”

When and How Joints Become Damaged

“All joints go undergo stress and strain,” Kelleher stated. “As long as we stay within [what’s called] the ‘elastic region’ – below the ‘yield point’ – the joint can accommodate for repetitive stress and strain. If we start working beyond the yield point – in the ‘plastic region’ – this is where things don’t recover. If we keep accumulating repetitive injury or an acute injury after the yield point in the plastic region, the joint can’t recover anymore. Whatever damage occurs is not going to be fixed or repaired.”

As one might imagine, the most common cause of joint disease in horses is brought on by repetitive stress and strain over time, leading to deterioration in the joint. “It’s the normal, everyday wear and tear that the horse places on his joints by doing his job,” Kelleher explained. “It doesn’t matter [the discipline]. In the course of a horse's job, he will accumulate stress and strain.”

In comparison, joint disease can also be caused by an acute overload injury – a bad step, a trip, or some sort of similar one-time occurrence that pushes the joint past the yield point. “Any movement or load from which the joint can’t recover, a sudden exceeding of the joint’s capacity to recover,” Kelleher clarified.

Whether the joint disease is caused by repetitive use or a single injury, the resulting damage is referred to as osteoarthritis. “All of the parts of the joint – synovial membrane, joint capsule, articular cartilage, subchondral bone – can have injury that leads to osteoarthritis. The cartilage can be worn away or torn or fractured. Subchondral bone can be bruised or fractured. The synovial membrane and the joint capsule can be stretched or torn. And then the synovial fluid serves as a marker of how much damage has occurred there.”

Any injury to any of the parts of the joint will result in inflammation, which creates inflammatory proteins and inflammatory waste products that build up in the joint. “If we exceed the membrane’s ability to get rid of all that waste product, the inflammation will progress and deteriorate and degenerate the joint.”

“Synovial fluid is our mirror into the joint’s soul, so to speak,” Kelleher observed. “It reflects the health of the joint. In normal situations, it should be clear and colorless or a faint yellow liquid and should be thick and viscous. There are no red cells, very few white cells, and very little protein. As the health of the joint deteriorates, these markers change, and by evaluating some of the fluid markers, we can see how much damage the joint may have incurred.”

About Dr. Maureen Kelleher

Dr. Maureen Kelleher earned her Doctor of Veterinary Medicine at the University of California, Davis in 2006. She then completed an internship at Pioneer Equine Hospital in Oakdale, California, and a residency in equine surgery at University of California, Davis. Before joining the EMC, Dr. Kelleher gained years of experience in equine private practice in California with a focus on equine sports medicine and lameness, advanced diagnostic imaging, and acupuncture. She became a certified veterinary acupuncturist in 2010 and earned Diplomate status with the American College of Veterinary Surgeons in 2013. Dr. Kelleher focuses on the assessment and non-surgical treatment of performance-limiting problems in sport horses. She works closely with EMC's therapeutic farrier team and its medicine and surgery teams, utilizing advanced diagnostic imaging capabilities to provide equine patients with superior care.