Research In Action: Shedding Light On The Age-Old Mystery Of Early Pregnancy Loss In Mares

© Copyright 2025 Paulick Report/Blenheim Publishing. Reprinted With Permission.

For many breeders and broodmare managers, there can often be a moment or two of holding your breath during some of the key ultrasounds in a mare’s pregnancy. Anyone who has spent time on a farm knows there are seemingly infinite opportunities for things to go wrong, and many moments when the mating dreamed up by a breeder fails to result in a healthy adult.

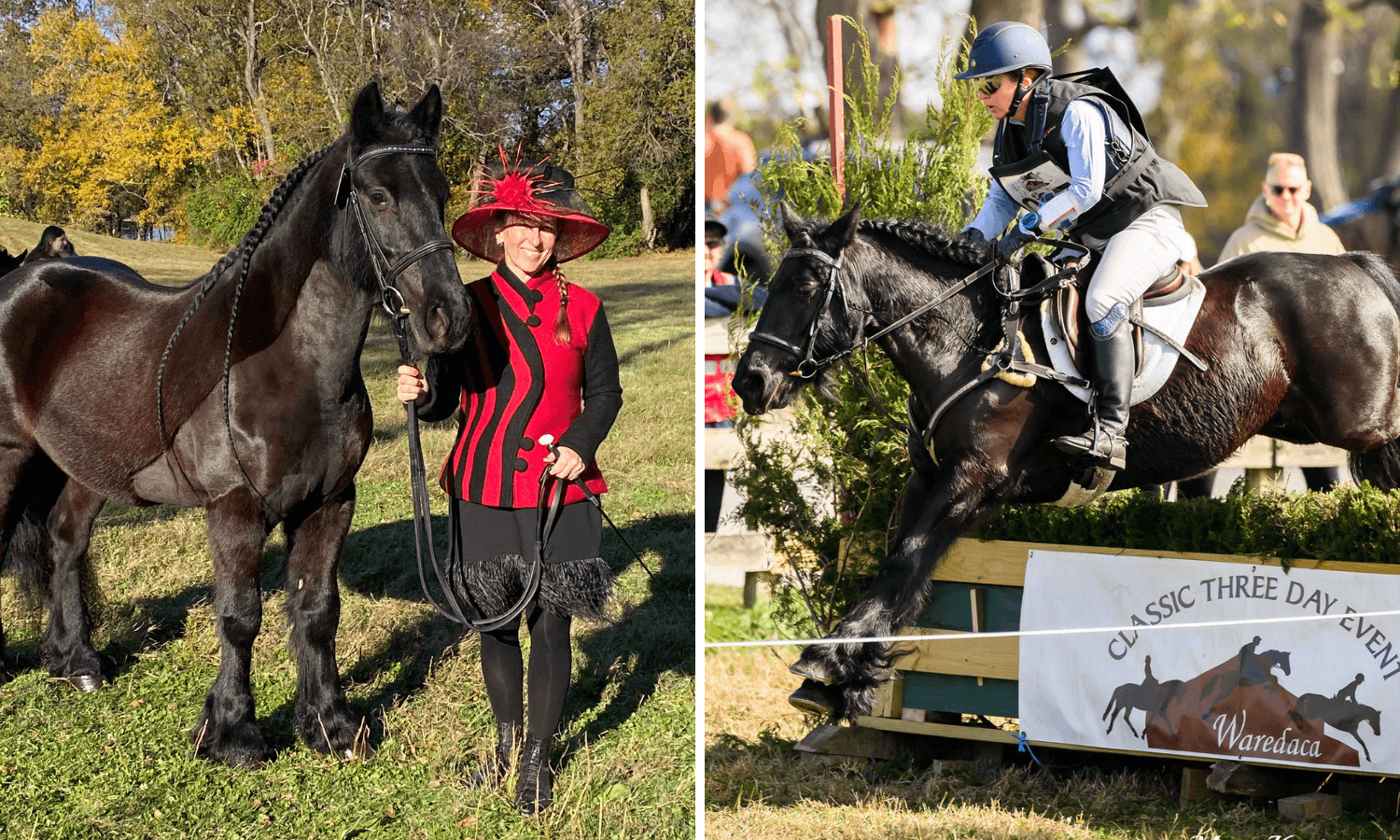

Dr. Mandi de Mestre, director of the Cornell Baker Institute for Animal Health, remembers those moments all too well. When she was still a clinical practitioner in her native Australia and England, she was often the person responsible for delivering bad news about a pregnant mare.

“You’d scan and they’re pregnant, and you’d scan her two weeks later and she’s not,” said de Mestre. “The client would say, ‘Oh no, what’s happened?’ and you’re like, ‘Well…I don’t know.’”

When a mare loses a pregnancy in the later stages, something about the fetus or the placenta can provide clues about what happened. But in those early weeks, there’s often not much evidence to explain the loss. In fact, in searching clinical records, de Mestre discovered 80 percent of early pregnancy losses weren’t connected with a cause by the treating veterinarian. When she made the pivot to the research world, unlocking the contents of what she calls the “black box” of early pregnancy loss became her central focus. Previous research had looked at the mare’s reproductive tract in hopes of discovering something that made the environment inhospitable.

“What I noticed in the literature is very few people had looked at the qualities of the embryo itself, and I thought of the embryo as having some inherent qualities that may be separate to the mare’s ability of maintaining or losing that pregnancy,” she said. “That led to an obvious question – what about the genetic qualities of that embryo?”

Most people think about reproduction as a process by which the mare and stallion’s DNA are copied, each contributing 50 percent to the resulting foal. Not only is the ratio not always that even, but there are lots of situations where the copying and collating process can go wrong. Embryos can end up with extra chromosomes which may result in birth defects or which may kill the pregnancy before it gets anywhere close to term. In a paper published several years ago, de Mestre discovered that up to 20 percent of clinical cases of early pregnancy loss were associated with an abnormal number of chromosomes. Recently, she wanted to build on that work and learn more about what kinds of chromosomal errors were happening, so she came to the Grayson-Jockey Club Research Foundation for help.

The foundation funds equine research that benefits all horses, not just Thoroughbreds. Since its creation in 1940, the organization has provided more than $44.4 million to fund over 450 projects at 48 universities internationally.

de Mestre’s Grayson-funded project accepts embryos submitted by veterinarians and farm managers in the field. After an ultrasound shows that an embryo is either dead or not viable early in the pregnancy, practicing veterinarians can administer prostaglandin and lavage the uterus, allowing them to collect the tissue. de Mestre’s team is then able to look at the genetic sequence of those embryos. This project focuses on embryos that have a gain or loss of a half a chromosome, as well as those that have an extra set of chromosomes (each cell in the embryo has 96 chromosomes, or three sets of 32, instead of two sets of 32). Together, those genetic disorders make up half of all the causes that relate to early pregnancy loss. The Grayson-funded project deals primarily with Thoroughbred mares, but de Mestre has seen similar rates of these genetic errors in Warmbloods, too.

“One of the two main aims of the Grayson project was to look at the prevalence of these types of errors in American horses, because we haven’t done that before. We’d only done it in the UK with primarily mares mated by natural cover,” she said. “The next question was, 'What are the origins of this?' Because if we’re going to try and solve this, we need to know why they happen.”

Embryos that end up with three sets of chromosomes instead of two are often the result of something called polyspermia, in which an egg is fertilized by two sperm instead of one. Usually, the egg creates a chemical reaction after it’s fertilized that prevents another sperm from being able to fertilize, which hints there may be an issue with the egg. There could also be errors that happen in either the egg or the sperm at the time chromosome sets are pulled apart for fertilization. The other option is that the copy error doesn’t happen until after the embryo begins growing and cells are dividing to make it bigger.

Much of this research overlaps with similar questions in human pregnancy loss, and work in each species could help the other. Doctors encourage women to take folic acid supplements, which have been associated with a reduction in genetic copying errors. de Mestre is hopeful there could be nutritional solutions to these issues in horses once they’re better-defined, also. If nothing else, identifying mares or matings that are associated with higher rates of genetic errors could guide breeders’ decisions about crosses, or about whether to keep a horse in production.

Her current research is projected to continue into spring of next year.

The next step in the process will be developing diagnostic tests that could provide owners with data on whether a gene-copying error is to blame for early pregnancy loss. This could reduce the need to treat the mare for suspected infections or hormone deficiencies, which are often initially blamed for pregnancy losses. Those tests could also pave the way for better diagnostics in the human medical world too, because as it turns out, horses and humans have a lot in common.

“What’s interesting is what we call the embryonic pace (how fast an embryo develops) differs between different species,” said de Mestre. “So you can imagine in a mouse, they only have a three-week pregnancy, so the pace at which the embryo develops is super fast and very, very different [from ours]. Horses and humans have a really similar pace of development, with nine months and 11 months in gestation length, and when we look at the time it takes for milestone embryonic features to appear in the two species, they’re very similar as well. If we look at the individual chromosomes in the horse and we paint them against which chromosomes they are in humans, what we find is remarkably about 60 percent of the horse chromosomes have an exact match to one human chromosome.”

If you are a practicing veterinarian who wants to submit an embryo to de Mestre’s project, you can reach her research team here.

Grayson-Jockey Club Research Foundation

Grayson-Jockey Club Research Foundation is traditionally the nation's leading source of private funding for equine medical research that benefits all breeds of horses. Since 1940, Grayson has provided nearly $42.3 million to underwrite more than 437 projects at 48 universities. Additional information about the foundation is available at grayson-jockeyclub.org.