Lessons in Listening with Kim Walnes, The Gray Goose, and Gideon Goodheart

“All of life is sentient, and all of life communicates all the time. We have separated ourselves from it. We deny it, but the capacity to hear is there as is the capacity to send. And so the thing becomes as an adult, then, to get back to that place, which is really about intuition.”

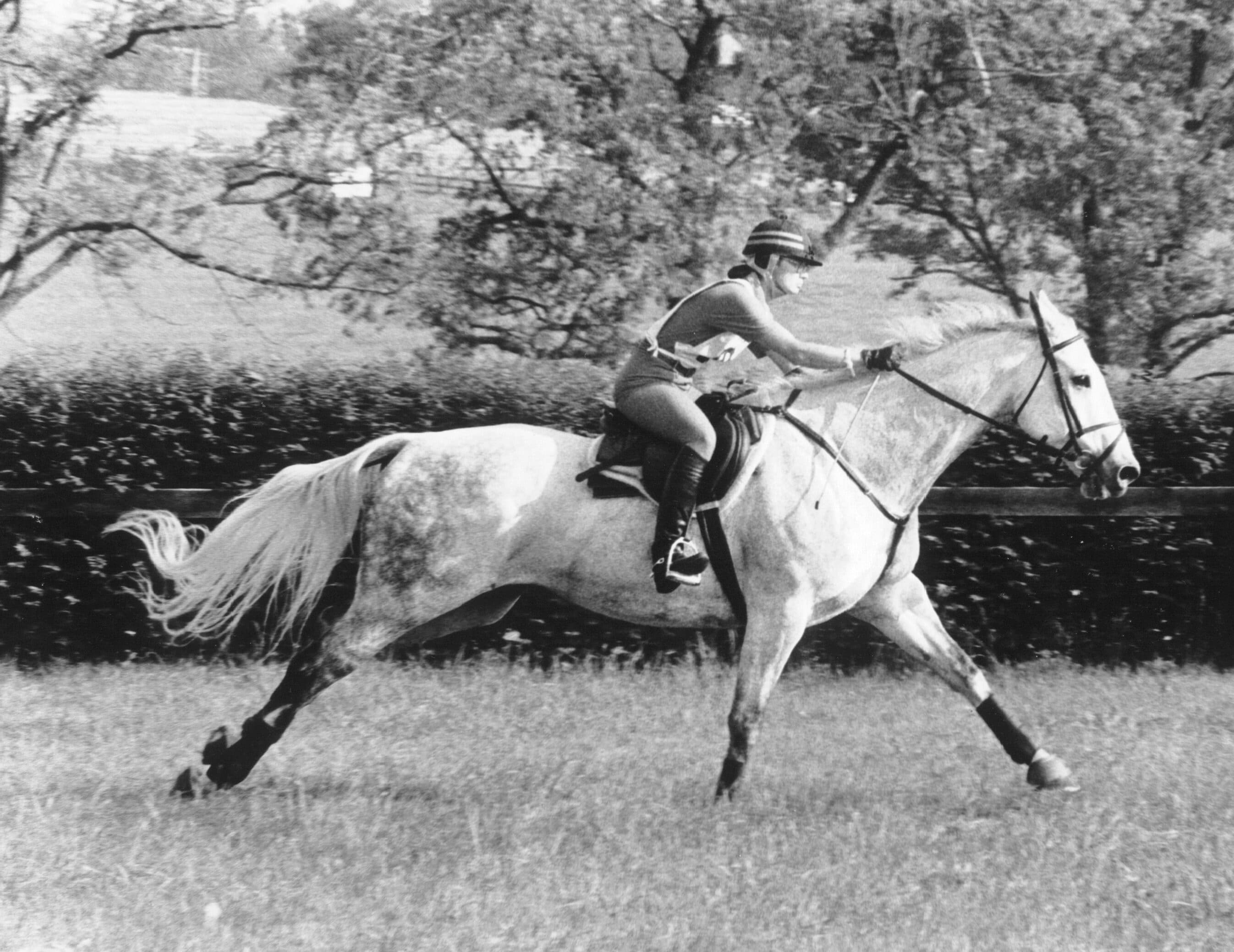

Kim Walnes has spent more than half a lifetime listening to and communicating with horses. Her journey both outward to the world of international-level eventing and inward back to an intuitive understanding of animals began in her partnership with the legendary, Irish-bred gelding The Gray Goose, with whom Walnes won Rolex in 1982 as well as the individual and team bronze medals at the World Championships in Luhmuhlen, Germany the same year.

“The Gray Goose was quite the teaching horse. He was a made teacher with a capital ‘T,’’’ says Walnes. “Pretty much nothing conventional worked with Gray. I had to figure out lots of different things.”

Walnes first began riding Gray in Ireland where she and her then-husband, Jack, were living in the mid-1970s. Even though Gray dumped her on a regular basis and proved to have a challenging personality, Walnes – who was recovering from a tailbone injury at the time – found his long back comfortable to ride, and she eventually brought him back to the United States with her along with a mare sired by the same Thoroughbred stallion, Hill Tarquin. While, at the beginning of their partnership, every ride on the 6-year-old Gray was a struggle, the two began moving up the levels. The Gray found his calling on the cross-country course, and while he was an awkward horse around the barn, stumbling and tripping all the time, Walnes soon discovered that “when he was running and jumping, he was grace personified.” In fact, she named him The Gray Goose “because he was poetry in flight, when he was galloping, but clumsy on the ground.”

In 1979, Walnes and Gray finished the Intermediate-level cross-country at Lexington (slightly modified from the 1978 World Championships) and were the only pair to make the time. As a result, they were invited to train with the United States Equestrian Team and compete with the team in Europe the following year.

In spite of all these successes, the relationship between Walnes and Gray was still rocky. “Every day was a battle,“ Walnes recalls. It was not until she began riding with Sally Swift in the early 1980s that Walnes felt her partnership with the gelding reached its true potential. By that time, Walnes had already been to Europe with the USET but she was willing to dial herself back down to basics if it meant improving her communication with Gray.

Walnes recalls that one day, her daughter’s pony club instructor invited her and Gray to a clinic with Swift. “I was the only adult riding in the clinic. It was all kids. And I went early because I always go early to clinics to learn as much as I can. And as I watched Sally teach these kids, I had to go into the tackroom and cry because finally I had found someone who taught in a way that I could understand.”

What Swift taught Walnes was how to ride by feel and how to both realize and release the defense mechanisms that her body had developed in response to injury; mechanisms that had subconsciously interfered with her riding.

“I am primarily a kinetic learner. Swift taught in a kinetic, feeling way. She would put your foot in the right place, and then she explained why it should be there and gave you the feeling of it. She said to me, ‘The pain that is preventing you from sitting all the way in your seat is not coming from your broken tailbone. That has healed. What it’s coming from are the protection patterns that your body has held onto that is causing tight muscles, which are causing bone pain.’” While Walnes at first resisted Swift's explanation, she decided to give Swift's methods a try.

“[Sally] showed m

e how to release those protection patterns, and when I let go of my seat and was able to be soft and pliant, [Gray] became a completely different horse.”

Most riders who have already competed at the international level might balk at the prospect of returning to the drawing board and starting again from scratch, but Walnes credits her subsequent achievements with Gray to her willingness to revise her assumptions and techniques.

“I’ve always been a person who stepped outside the box. Because my mind works differently than a lot of people. I just thought anything that’s going to help me and my relationship with my horse, I’m going to embrace it.”

Walnes' receptivity to Swift's intervention proved a turning point in her career. Her adjustments greatly impacted Gray’s ability to perform, and the two went on to win Rolex in 1982, compete at Badminton in 1983, serve as alternates for the 1984 Olympics, finish second at Boekelo in 1985, and represent the US at the World Championships in Australia in 1986.

Speaking of a photograph of the two banking an oxer at the 1986 World Championships, Walnes says: “It shows just how far an awkward horse can come when taught how to feel all his body parts and how to use them properly. What he did there was so incredibly clever, and saved both of us, for it was incredibly slick on course, and he slid into that fence as he took off. It was quite wide, and by banking like that, he got us across safely, though he did pull a hind shoe in the process.”

The epiphany that Walnes reached in her relationship with Gray also impacted her teaching and approach to training with her own students. “I went home to my students after that clinic [with Sally Swift] and I apologized to each and every one of them, and I said: ‘Look, here’s the deal. I have just learned a whole new way of being with horses and a whole new way of teaching. It’s so much better than anything that I’ve been working with. I can’t do the other way anymore. I can’t do that because it’s not fair to the horses. It’s not fair to you, and it’s not fair to me.”

A large part of Walnes' training philosophy now involves listening to the horses themselves. “I say to the horses: ‘We welcome your input. I ask that you do it in a gentle way.’” Walnes has discovered that once horses understand that their riders respect their feedback, they relax and become more receptive to guidance.

The techniques that Walnes has adapted from her lessons with Swift and also from Linda Tellington-Jones have broadened into a greater appreciation for the insight that animals can offer to humans, whether these have to do with riding or not.

“I remember there was a student who just, every lesson was a repetition of the one before when it came to feel. And I kept trying various things to help her feel the information her horse was giving her. We were halted. And the horse rolled his eyeball at me, and he said in my head, ‘She’s never going to feel until she sorts the rest of her life out.’ And I mentally said back to the horse, ‘That’s not my job. My job is to help her ride better.’ And he said, with great patience, ‘She’s not going to be able to do that until she gets the rest of her life together.’”

The feedback loop between riding and life has been a guiding thread in the rest of Walnes' career. With the urging of her current horse Gideon Goodheart – Gray’s grand-nephew and the third generation of Walnes' breeding program – she went through a two-year course on life coaching and subsequently began offering life-coaching sessions in addition to riding clinics. Throughout all aspects of her teaching and coaching, Walnes emphasizes the importance of feeling safe and balanced, whether that feeling is achieved in a person’s own body or on a horse.

“Horses are fluid,” says Walnes. “We need to be fluid as well. We need to know where to hold and where to let go.”

Time and again, Walnes has seen this self-awareness within the rider translate into a more relaxed and responsive horse.

“Now we are going to pay attention to what your horse has to say to you in response to the changes that you’re making,” Walnes says to her students. “And usually within about four strides, [the horses’] backs relax, their spines start swinging. The head goes down, the tail starts swinging. And the riders are like, ‘Oh!’ And that’s how I start people out.”

Walnes' remarkable journey is the subject of a recent documentary film project called “Mother Goose: The Kim Walnes Story.” The trailer for the film was part of the 2021 Equus Film and Arts Festival and while the project has stalled momentarily, Walnes is actively seeking filmmakers and documentary producers to see it to completion.