Thinking Like a Horse with Aaron Vale at the 2014 ICP Ocala Symposium

Aaron Vale is a highly experienced and current show jump competitor who rides at the HITS shows in Ocala during the winter and at shows as far north as Virginia in the summer. For example, on the German stallion Spirit of Alena, Aaron won the HITS Grand Prix class on February 9, two days before his presentation for the USEA at the Instructors’ Certification Program (ICP) 2014 Ocala Symposium at Betsy Watkins’ Longwood Farm South. He is also the instructor and coach of many other jumper riders, including his wife.

Audience members, as well as the riders, listened very closely as Aaron taught 19 rider and horse pairs in the new Grand Prix show jump arena at Longwood. His focus on those riders and their horses was consummate. The exercises he chose and the directive, corrective, and complimentary words he expressed moment-by-moment said it all.

Here, first, are some of Aaron’s basics for show jump riding and training:

- Select a stirrup length that is middling—not so long as your dressage length and not so short as your cross-country length. For show jumping, you need the balance and enough length of leg for the “dressage between fences” as well as, occasionally, for more “go.” “Put the dressage and the jumping together,” Aaron advised.

- Select jumping exercises which, when well ridden, improve your and your horse’s skills. Focusing on riding smoothly and effectively will improve your position.

- Break each exercise into segments, if necessary, and learn how to ride each segment correctly. Then, put all segments together.

- Jump with energy from a deep distance, using your leg when necessary to get a cleaner jumping effort. “Sit up and believe in that deep spot!”

- “Don’t rush or hurry your horse. Hurrying leads to lack of balance. Wait with his steps, and keep your leg on.”

- Teach your horse (and yourself) to move in somewhat longer, “looser” strides as well as somewhat shorter, gathered strides. You will need them both during your jump course riding. A looser stride is “a bit more forward. If you start too slow and controlled, you can’t actually collect. If you start too collected, you are apt to lengthen or flatten eventually.”

- Decide on your track and ride that. Don’t let your horse fall in on the turns. Make a friend of your inside leg.

Throughout the day, Aaron used similar exercises with his four groups, Training through Intermediate/Advanced, increasing jump heights for the mature-stage horses. Each exercise required essential skills. He created jumping situations requiring the rider to develop sufficient balance and pace, communication, and horse adjustability. Throughout the day, he requested riders to go to a deep distance,

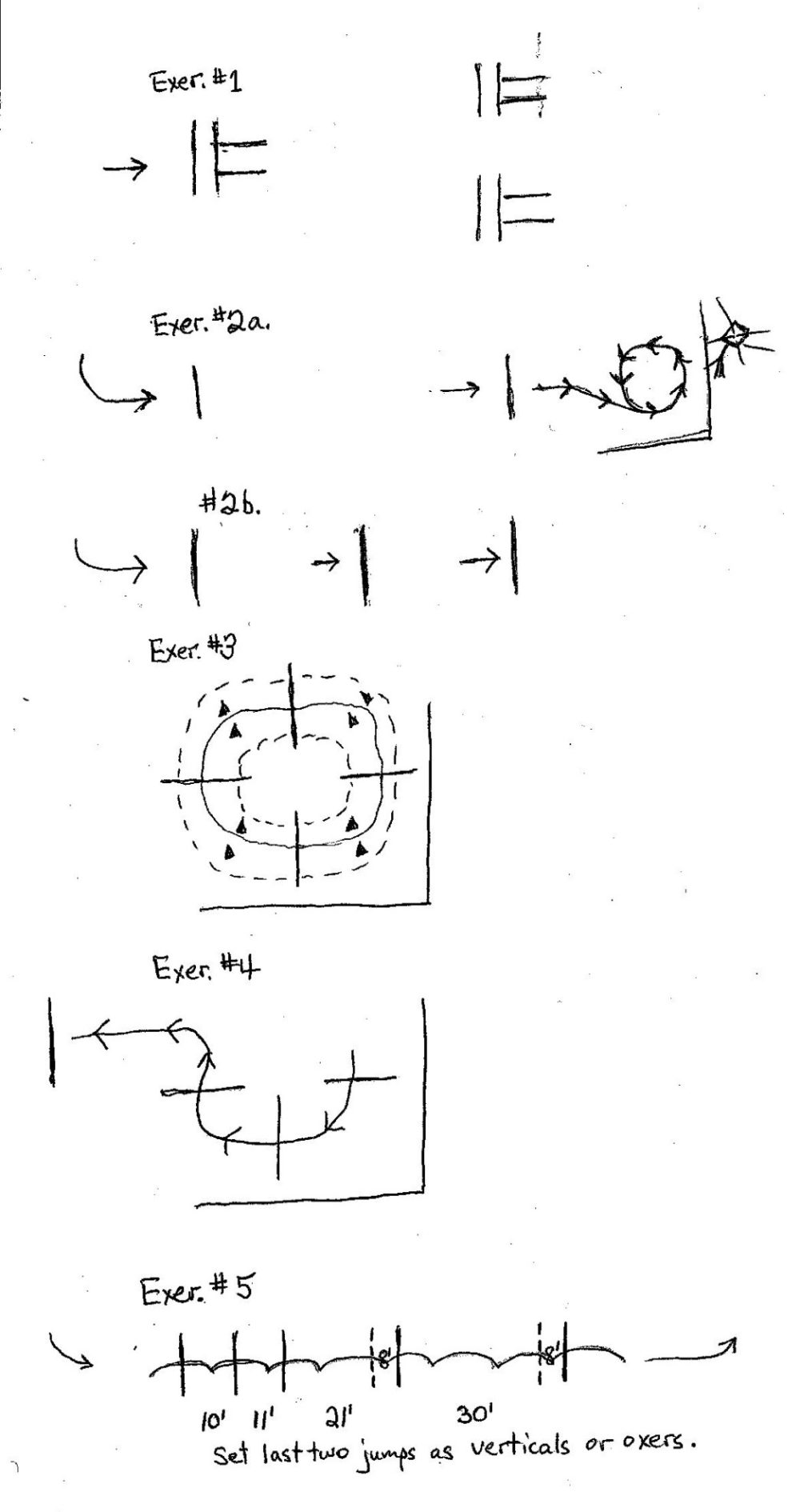

Exercise #1 – Purposes: Consistent balance and tempo; control of stride length; horse straightness to fences.

Place two rails on the ground for two trot steps between them, with two similarly set rail pairs about seven canter strides away, one pair slightly to the left and the other slightly to the right. Add two other parallel rails after and perpendicular to each second rail, centered about 5 feet apart to invite straightness. After riders trotted over these, Aaron raised the second rail of each second pair to a 2’3” vertical. He asked all riders when trotting over these verticals to get the two steps, not one, between the rail and the vertical. Then with all three fences set as verticals and with no ground rails, he asked for a short enough canter stride to and beyond the first vertical and a deep distance to each of the other two verticals. Somewhat unusually, he asked riders to leg yield in canter to the left vertical if the horse landed after the first fence on the right lead and to half-pass in canter to the left vertical if the horse landed after the first on his left lead. His goal was to keep the horse’s body square to the fences and in the air over them.

Exercise #2 – Purposes: Forward riding to the base of the fences; upon landing, control of gait and track; full attention to all segments of the exercise, regardless.

A. Set up two fences for a long and steady six strides on the left lead; land after the second fence and develop a dressage-like left lead canter circle in that corner of the arena – a corner which at Longwood included a loud public address speaker. Aaron was adamant that riders approach the first fence with enough energy and pace that the second three strides in the line could be steady. Then, he asked riders to approach at that same pace while closing that stride up after the first fence to get seven. As he said, “Anybody can go slow to the first fence to get seven.”

For the two horses who were spooked by the speaker, he advised riding forward to the first fence, then collecting the stride as they approached the second fence. Regardless of the quality of the jumping, he asked those riders to land and find a track after the second fence enough to the right and enough into that arena corner for a well-formed left canter circle. Use your left leg/spur to put the horse more to the right before circling left. To other riders, he advised a shorter canter after the second fence for a better flying change right-to-left. It may seem like a simple exercise, but getting and keeping the balance and pace for the requested number of strides and then for the well-formed left canter circling is not so easy.

B. Aaron then set a straight three-fence line with equal distances between the fences and asked for five-to-five strides and then four-to-five strides. To ride the four-to-five, he asked the riders to ride well balanced and forward to the first fence and get a “managed” four, and then a “more managed” five. In other words, ride in with balance and energy and, along the line, ride to gradually contain that energy so that the stride is sufficiently shortened for the five.

Here is how Aaron analyzed one rider’s four-to-five line that ended up being four-to-four: “She got deep to the first fence which made her chase to the second to get the four; then, her stride was not short enough for the five between fences two and three.” The rider processed this information so that she then rode a better balanced stride to the first fence, gathered for the four, and gathered more for the five. Nicely done. Another rider rode too open and with too much pace to the first fence, so she had to slow too much for the four; the next time, as advised, she rode slower and better balanced to the first fence and got the four easily.

Exercise #3 – Purposes: Development of partnership of horse and rider; sharper eye, better feel; rider control of line and stride length.

This exercise is famously known as the “circle of death,” and probably all of us have ridden it and survived. Place four sets of standards at three, six, nine, and 12 o’clock on a circular track with a curved line distance of about 60 feet from the middle of one fence to the middle of the next. Start with the rails on the ground. Especially for early-stage horses and riders, set four pairs of small cones to define a circular track between the fences and directed toward the middle of each one. Ask riders to ride first outside of the cones on a large circle over the outer side of the rails/fences, then between the cones on a smaller circle to the fences’ middle, and then, if possible, inside the cones on the smallest circle to the inside of each fence; then, back out to each larger circle. For mature-stage horses and riders, remove these pairs of cones and ask for smaller or larger circles over the fences without the aid of these track markers.

“Green horses should be ridden ‘basic and forward’ over this pinwheel,” Aaron said. Give your horse time to figure out the idea of holding the canter bend and staying on the inside lead. If he acts confused by the exercise, drops out of canter, or does not retain the inside lead, trot collected—not running—over the fences. When you return to the canter, use your inside leg at the girth to better maintain the inside bend/lead while you ride a consistent stride length and tempo. If you are having trouble loosening and bending your horse, trot and canter him over a single rail until he becomes more supple on each side, then add in another rail.

Assuming that you have set the four fences equidistant from each other, ride the same number of strides between fences. With more developed horses, on the same track shorten and lengthen the stride to add or reduce the number of strides between fences. One Advanced horse and rider pair cantered the same circle track in seven strides and then in six, five, and four strides between fences all in good balance. Regardless of the number/length of strides and regardless of level of horse, do not hurry your horse in this exercise. Confirm your gait with a quiet seat and hand while allowing the horse enough freedom and looseness that the exercise, though monitored, feels easy and comfortable. To ride the smallest circle, focus constantly with your eyes upon the upcoming jump (see photo at top of article), and determine by feel whether your horse is able to canter, jump, and land easily on that track or whether you must consciously move his shoulders inward over the track with your outside rein and leg. If the latter, should you do that before taking off , after landing, or both? Experiment to find out. Notice also whether your horse finds it harder to circle-jump on one lead than on the other. If so, with the help of some eyes on the ground, determine why this is and how you should develop that lead further.

Exercise #4 – Purpose: Adjustability and balance of both horse and rider.

After cantering three of the circle fences on the right lead, turn left to a fence five strides away. The difficulty is finding the best balance and timing for the left turn after the right lead over the third fence. Not surprisingly, horses and riders handled this challenge with some variety at first. Some landed going right after the third fence

and then changed leads only in front. Others trotted a step and then cantered left, which is preferable, according to Aaron. Another rider spiraled her upper body slightly to the left over the third fence, intimating to her horse, “We’re going to go left.” The result was the horse landed and lightly lifted his shoulders left into the left lead, cantered evenly to the fourth fence, and completed the exercise, as requested, with a dressage canter circle to the left. Well done!

With a couple of horses who were “running” through the first three fences in this exercise, Aaron asked those riders to jump, halt, and back up after each of those fences. “Break your jumping exercises into pieces, if necessary, so that you train your riders and horses so that they can go shorter and more adjustably to closer distances.” The result was clearly a better ride whole. As rider Zara Flores-Kinney has reported, “I was so glad that Aaron worked a lot on shortening my mare's stride and balancing her up in front of the jumps because we then had a double-clear Preliminary stadium round at Rocking Horse the next weekend!”

Exercise #5 – Purpose: Correct and consistent balance and pace on a gymnastic line designed to reward the horse for quickness off the ground and athleticism.

This line included two bounces set at ten feet and 11 feet, a 21-foot distance for one stride, and a 30-foot distance for two strides. The significant addition was a ground rail set at about 8 feet in front of each of the last two fences. For these ground rails, Aaron uses two rails set next to each other, not just one, because he has found that horses are more likely to leave out that stride if they see only one rail.

Every horse jumping through this gymnastic line jumped better due to the effect of the ground rails. Aaron teaches his own horses to jump from deep distances with enough quickness off the ground to leave up the front rail and with enough power and flight to leave up the back rail. This use of ground rails is one of the ways he develops those jumping skills in his horses. You can, too.

Let’s look at five rider and horse pairs to reveal five different positive effects of this gymnastic exercise.

- First, a young woman on an eager, quick, and sometimes tense horse. With Aaron’s suggestions, the rider had made good use during her circle-jump riding to calm her horse via cantering and jumping on a curved track by using her inside leg and inside rein to develop the bend in each direction and by softening the reins every time her horse began to relax. Also, she “stayed tall” for the last stride to every deep distance. To the gymnastic, her horse was again too fast. Aaron asked her to allow some “looser” strides when not heading toward a fence, to avoid riding backward, and to give in the last stride. He also advised raising her hands from their low position so that the horse could “lift his withers” when jumping. Finally, he asked the rider to note the number of raised fingers of a man standing to the left of the last fence. This last request improved both her eyes and her position through the line; her pace was still too fast but the horse was not careless. About this rider’s longer-term goal of developing a more consistently relaxed horse for jumping, Aaron said to her, “It’s okay if it’s not a skill today. It’s getting better!”

- One man’s rhythmic and long-strided horse had no trouble with the idea or the execution of this gymnastic exercise. However, Aaron wanted the horse a little sharper and more powerful, though not faster, over the last rail and off the ground at the last fence. He asked the rider only to “be more active with your lower leg” over the rail and upon take-off. The good timing and effectiveness of this rider’s aid put his horse’s last jumps in the “A” range. The before- and-after jumps demonstrated to us onlookers the difference between “jumping from a deep distance” and “jumping with energy from a deep distance.”

- Another man was riding a stallion who can be, let us say, cheeky! The horse’s acceptance of the connection had been intermittent throughout earlier exercises. However, once the horse was presented to and understood this gymnastic line, his focused attention was exemplary. To onlookers, the horse went from “just jumping” to “wow, can he jump!” The set-up of fences and placing rails was sufficiently complex to elicit superior carefulness, balance, rhythm, pace, and jumping from this capable horse.

- Another young woman was riding a willing and competent Thoroughbred gelding. She has been experimenting with lightening her hands and lifting her seat to limit his leaning and to allow him to soften his back and neck over the fences. During the first exercises, she had begun, at Aaron’s request, to soften her connection during the last stride before each fence of the circle-jumping. Then, over the straight-line exercises, she was “landing, organizing, and giving.” The result was a softer ride to her jumps from the base. To the gymnastic line, Aaron suggested that she ride looser to the first fence. Then, with the comfortably set distances of the gymnastic line, he encouraged her to soften her hands between each of the fences. The last time through, he said, “The better he gets, give more so that he can put his head down over the jumps.” As a result, over the last fence the horse’s supple and athletic jump was notable.

- Finally, another young woman was riding her long, tall, Thoroughbred gelding who was formerly famous for leaving out strides, she said. As a result, she has become accustomed to containing the horse with her reins and not riding quite forward enough. So, during her first ride through this gymnastic line, she landed after the second-to-last fence with him well in her hands so that he would be sure to take two strides there, not just one. But as a result of that contained short stride upon landing, the horse’s second stride over the ground rail and to the base of the last oxer was—had to be—long and flat. So, his haunches were not under him for the jumping effort and he took down the front panel.

Aaron advised her simply to ride with more leg and less hand in an energetic, balanced, and somewhat longer stride to the bounces at the beginning of the gymnastic line. Then, land after the second-to-last fence with a normal stride there to a shorter, better balanced stride over the rail to the last fence. With this approach, the horse lifted his front end, pushed from behind, and basculed over that last fence in textbook style. Susannah Lansdale reports that “he felt like an entirely different horse over that fence. He arced up over it, and the ride felt easy!”

Especially for event horses who don’t always want to “wait,” Aaron advises using the above exercises to school the horse and the rider to learn to wait and jump from deep distances. Judging the front of the fence and rocking back for the jumping should become second nature to both horse and rider. To set up horses for riders who don’t easily see the distance to the placing rail eight feet in front of a fence, set another fence at about 21 feet in front of that second one. For horses who collect well, school them to “free up and lengthen”; for horses who naturally travel long, school them to shorten.

Aaron uses flatwork to develop his horses’ rideability, using lateral work both at home and on courses. When he rides only on the flat, he lowers his stirrups from their show jump length. He jumps most of his developing horses about twice a week, whereas his developed Grand Prix horses jump less often. With a young horse, he “stretches him occasionally” by jumping higher at home than in classes. Mostly, though, he uses gymnastics (including the eight-foot placing rail), lower fences, and stride lengthening and shortening to develop a horse’s jumping ability. For about a week or ten days after a Grand Prix course ride, Aaron does no jumping with that horse. Then, he adds in some jumping in his preparation for that horse’s next show. So, depending upon each horse and upon the skill(s) he wants to develop, improve, or confirm, Aaron makes his decisions about how often and how high to jump. Base your own schooling and competing decisions upon what you have learned from close attention to each horse. How sound is the horse? What are the skills which you and that horse need to develop? How does that horse go when fresh? When tired?

Clearly, Aaron’s moniker “Thinks like a horse” was confirmed at the 2014 ICP Ocala Symposium at Longwood. Thank you, Aaron, for sharing with us the sound advice you have gleaned from your experience as a rider, trainer, and instructor!