Instructors’ Certification Program Jumping Symposium, 2009

Learning with Anne Kursinski: Part 1 of 2

Well-known American jumper competitor and instructor Anne Kursinski rides more as a zen master than as a dictator. While she is riding and jumping, her body is flexible yet still, her legs are close and quiet, her arms are following. She teaches, too, like a Zen master: with few, but exacting, words. Always observant, Anne invites her riders to sense through their bodies their relationship to the horse and to their united movement over the ground.

During three group show jump lessons with event riders early in 2009 at Betsy Watkins’ Longwood Farm in Ocala, Florida, Anne focused upon rider position and aids. Adopt a light seat with your back angled forward slightly in front of the vertical; relax your knees and sink your weight down through your heels; carry your elbows just in front of your ribs; ride on a short rein with your hands moving forward toward your horse’s mouth, not backwards toward your belt buckle. Anne uses the light seat for jumping because she teaches her horses to “mind my legs” and because, if she rides in a light seat, she still has the deep seat to go to when needed for emphasis. With respect to aids, Anne uses them in a Zen-like partnership with her horse. She says to her horse, “Let’s do this – together and well.” As Mark Phillips noted approvingly while watching Anne ride, “You ride with the horse’s movement, not against it.” So, visualizing that snapshot of the rider’s posture, let’s ask, “How well does that work when a horse is being difficult?”

A true story

During several sequences of related-fence lines, Karen O’Connor’s 10-year-old Rocket bolted forward toward some of the fences. As the jumps in front of him caught his eyes, his gait changed as though he was drawn forward by a magnet. Carrying his head and neck high against her hands and leaving out the last stride in a 4-stride line, he jumped sometimes like a stag. Having experienced something similar on the weekend prior during an event’s show jumping phase, Karen walked on the horse up to Anne and asked, “Would you like to get on him?”

What was Anne thinking as she said yes?

Anne is an optimist. In general, she believes that each horse can do more than we – and he! – now know, and that each rider can ride as she does herself. So, yes, Rocket sometimes looked possessed by the jumps ahead as he grabbed onto the bit, but also with Karen his canter looked easy and relaxed. How interesting, what fun to experiment with this able horse to find a way to “let a little air out,” to break through his attack mode, to help him discover how easy it is to go calmly, “normally.” In other words, Anne got on not knowing exactly how she could make a positive difference, but glad to try.

Immediately she took her light seat position. She invited the horse forward on an allowing rein, picking up and maintaining a quiet canter. In fact, Rocket cantered “nicely.” Throughout the first minute, at canter, she spoke to the horse: “I know you can do this quietly, calmly… I know you can add another stride…” With that quiet light seat and no leg, Anne cantered the horse on left and right curves among the jumps in the grassy arena. She cantered with a soft hand, “breathing with the reins,” moving the bit by using a little giving and taking and a little left rein, right rein as suited the apparent tone and balance of each moment. She circled at canter away from a jump or two. Then she did something she rarely does: she dropped to trot before jumping their first fence together. With her quiet light seat and the bit moving a little, the horse did not grab it…

After riding at canter and breaking to trot for some fences, Anne felt the horse beginning to understand what she had been saying to him: “You can do this – normally.” No roughness, no halting and backing – just changing the energy by slowing to trot, jumping a fence, then back to canter. After a couple of minutes, Anne felt that the horse was getting the feeling she was looking for: she found on the turns at canter she could hold the reins loosely, with her own balance rating the horse. In fact, his canter became soft, almost “pitter-patter.” Then at canter she jumped and turned and rode bending lines with the horse landing in the same good stride after the fences as before. Finally, she rode an outside line in 5 strides, dropping the reins entirely just before the second fence and raising her arms out from her sides! Even so, Rocket did not leave early, and he landed without rushing away.

For those four special minutes, the many spectators and other riders stood completely quiet, mesmerized.

When Anne rode to the first few fences, the horse considered anticipating – but didn’t. How so? >Anne initially altered the horse’s expectation and energy by dropping to trot before jumping. >She moved the bit softly in his mouth and avoided taking with her hands if the horse thought about rushing: in other words, she did not let him sucker her into changing her mind and sending him strongly forward. >She maintained the light seat, with stomach/center coming back when slowing or settling the horse – without dropping into the saddle to drive him. With time and good practice, thus a horse learns to “mind the leg” while the rider learns to “trust that the horse can pat the ground.”

Anne walked the horse back to Karen. Karen mounted, adopted that same light seat, and picked up that same canter. She then rode just as Anne had, producing several quiet jumping efforts where the horse’s canter was soft and his topline was appropriately flat and long. Since that day, Karen is confirming her partnership with the horse; they are working well together in their show jumping, whether she rides with her seat lighter or deeper.

So, a multi-layered portrait of success: one excellent rider inviting input from another excellent rider; a fresh and quietly experimental approach to the riding of the horse; the first rider focusing closely and then imitating immediately what she saw – willingly and competently. And a happy horse.

How does this optimist teach?

Quietly, patiently. Smiling at just the right moments. And, yes – sometimes frowning…!

Position and aids

See second paragraph above.

In her warm-up flatwork with all three groups of riders, Anne asked each rider for the mental focus and watchful eye to maintain even spacing as 7 to 9 of them worked together on a very large circle. A stickler for smooth and regular rhythm* and tempo*, Anne referred to the 6 mile/hour working trot. Find that with your horse, and keep it.

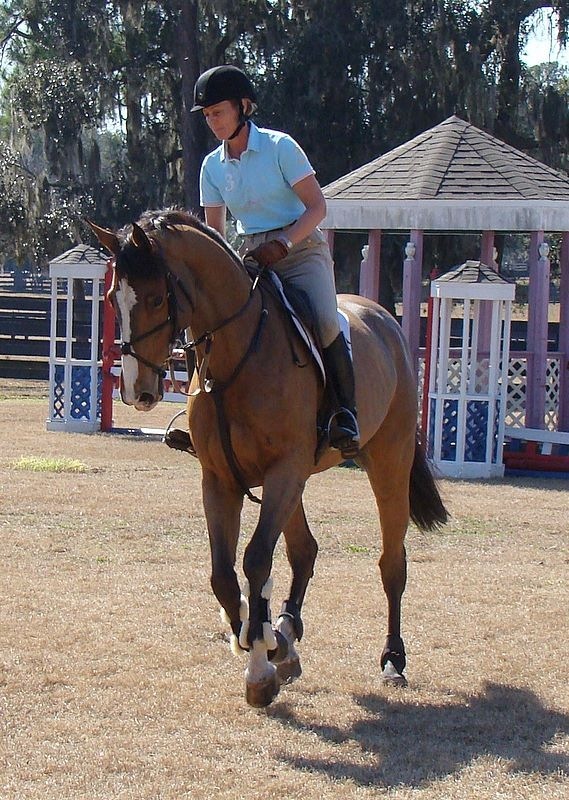

(Right: Anne works with one of the participant’s horses.)

In developing each regular and rhythmic gait, create appropriate responsiveness to your leg and your hand. Ride with the motion with a stretched-down leg and elastic arms, inviting the horse to take the bit with a long-enough neck. Soften your hands as soon as the horse does take the bit. Don’t pull his nose into his chest, shorten his topline, or overbend laterally. Many times Anne asked riders to “let the neck out” and to avoid taking too much with the inside hand, particularly at sitting trot and canter. Riding with the neck long enough does not mean inviting the horse to lean on your hand; rather, it allows the horse to move in self-carriage, using his neck to balance his body in a way appropriate to his stage of physical and mental development.

To develop the horse’s suppleness, balance, and obedience to the aids, include shoulder-in at sitting trot. Begin by using a long straight track along a rail for this work. As your horse matures in his mind and body, at canter add a small circle and upon return to the track maintain the small-circle bend and develop canter shoulder-in; then transition downward to shoulder-in sitting trot. Ride a half-circle, canter the other way, and repeat. Walk, and then add a long rein. If you note that your horse moves in haunches-in in one direction, say, to the left, use shoulder-in in that direction to strengthen his inside hind. Ride shoulder-in and haunches-in to the right, as well, to stretch the left side of his body as much as he normally stretches the right side. When you ride a lateral movement like shoulder-in, carry both of your hands slightly toward the inside of the bend.

Because Anne wanted her riders’ arms longer and reins shorter, she asked riders to tie a knot in their reins about halfway between the buckle and the bit and to hold the reins in front of that knot. She then returned to the flatwork and asked for sitting trot with no stirrups. She requested flexibility in the hips plus riding with the horse, not against him. To create the mental impression of the rider’s body moving with the horse’s motion, she asked riders to imagine that riding with hands in front of the knot “puts the hands in the rider’s back.” In other words, the whole body of each rider then works as a unit with each horse’s motion, the rider’s arms being a continuation of the reins with the hands working as a pair.

It is difficult to “teach” feeling, or even to describe feeling in words. An instructor’s value to you the rider lies in shaping your position and aids to produce moments of good movement – and then actively drawing your attention to how that feels. Use your eyes, too, to watch other riders and horses who are moving in balance over the ground.

Anne provided her riders with several techniques to acquire elements of the kind of feeling she prizes:

> Without stirrups at sitting trot and canter, allow your leg to drop down with a straighter thigh and a softer knee. This can result in a more centered, following seat.

> Ride on the flat holding the reins with your thumbs closer than your fingers to the bit, i.e. with your hands “turned over.” Holding the reins this way helps the rider discern the feeling of a soft, following contact. Then the rider is less likely to hang on the mouth with locked elbows.

> Experiment with holding the reins in front of a knot to quiet the hands and to ride as more of a whole-body unit with the horse. Take this whole-body feeling to the jumping.

> If you are not a beginner rider, ride over fences holding the reins with your hands turned over. Just before, over, and just after a jump, smoothly widen your arms so that each hand is about 12” out from your horse’s neck, still maintaining a soft connection. Follow his head and neck movement with your arms while your upper body is in normal jumping position. Practicing this will help you develop an independent seat for jumping.

When your arms follow the horse’s head and neck movement over the fence with a straight line from your elbow to the horse’s mouth and without your hands resting on the horse’s neck for your own balance, this is referred to as the automatic release.

* * * * *

Post script

*rhythm and tempo. For those riders and instructors who, like ICP, have adopted the German National Equestrian Federation and USDF lingo because we include formal dressage riding in our equestrian lives, number of strides per minute is tempo, whereas each gait’s distinctive number of beats per stride is rhythm (4 beat rhythm for walk, 2 for trot, 3 for canter, 4 for gallop, and 2 for reinback).

Look for Jumping Exercises, Part 2 of Learning with Anne Kursinski, to be presented this Friday in Eventing USA 2.0!